Church in the Time of Covid-19

*This was a presentation I made to the Pacific School of Religion alumni community as a webinar on April 7, 2020. I decided to publish it here because I have had a few ministry friends ask my thoughts on similar questions.

The question I’ve been asked to consider today is “What does it mean to be the church at this moment in history?” The most beautiful answers have begun with the most beautiful questions, so for today, I offer us some questions that may lead us to answers later.

President Velasquez-Levy has reminded us that the word “Apocalypse” in Greek can have the meaning “uncover or reveal”. We have since come to use the term to mean complete and final destruction or the end of times. Both are ways in which we can define this particular moment in history for the church as we know it in the here and now. We sit at the intersection of a revealing and the reality of an end.

Covid 19 and the sub-sequential Shelter-In-Place mandate has forced the church to more urgently address already shifting ideologies in our methods of praxis, our theological understanding of what it means to be the church, and our prophetic call as the church to come. I teach the Field Education class and I have become acutely aware that my current students came to PSR with a very different church in mind than the church they will graduate into. We are right now shaping them to be in a ministry that does not yet exist.

Before Covid 19, the question of transformation was generational. As Boomers and Gen Xers prepare the church for Millenials and Gen Z, I would ask my class of future pastors and faith leaders what must be done now in this generational tipping point? We already recognized that for the sake of the continuation of the Church, things cannot stay the same.

But now, in the time of Covid 19, because of rising Coronavirus cases that exponentially grow each day, because of major economic and social shifts taking place in our global society right now, because of the urgency of humanitarian needs, we cannot afford to wait for the generations to change. We can no longer talk about a changing church in theory. We cannot go back to what was and it may be too early in the crisis to plan for what the church could be. This liminal space is one ripe with both the death of the Church as we know it and the possibility of the rebirth of a new church to come. This my friends is the moment in which we find ourselves.

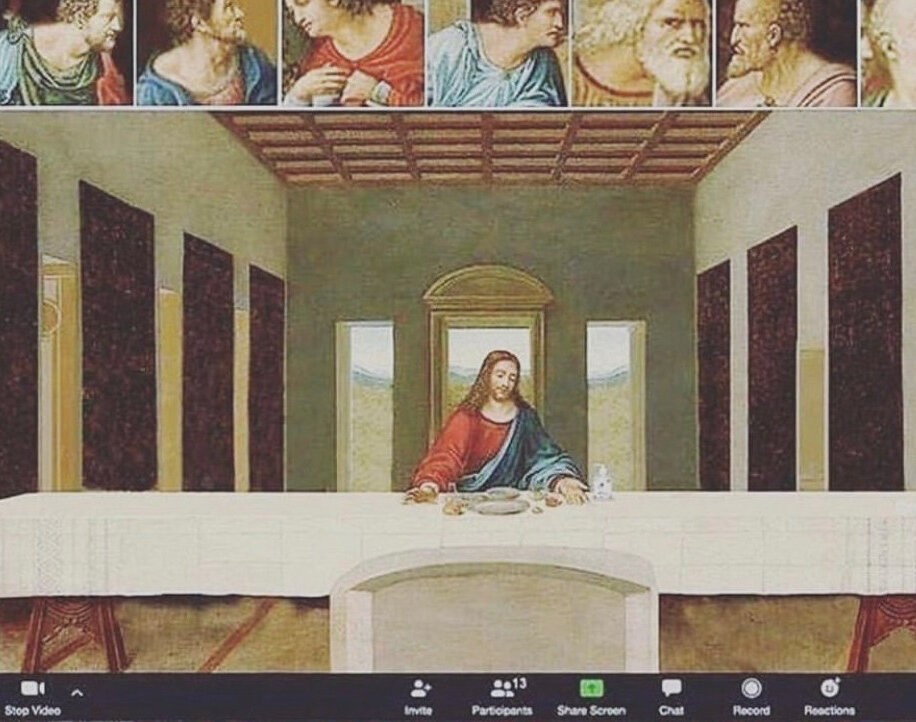

On a practical level, churches have had to make adjustments. Church leaders have been forced to become televangelist of sorts having to figure out how to transmit fellowship, community, worship, and divine presence over technology that feels distant and disembodied. Churches have wrestled with the best ways to pass the peace, unify the choir, and serve the Eucharist. I attend a mostly African American church, and I noticed the pastor switched his call and response from “turn to your neighbor and say…” to “Chat some someone Amen”. It’s an adjustment for sure. Churches have zoomed and YouTubed and Facebook lived their ways into people’s homes. Churches have had to consider how to make these online services accessible for those without internet access or for older members who may not be able to navigate these platforms as easily.

These practical adjustments have forced church leaders to examine in an urgent way what is essential to the life of the church? Is it that the elements are broken and shared from the same source together or can we use crackers and coffee from home? Is it that we are physically gathered together or is Zoom sufficient community? And whatever we decide is essential now, will those be essential once the crisis subsides? Said differently, what really matters to the Church AND does Church really matter?

Millennials and Gen Z have already been asking those questions, but Shelter-In-Place has now brought those questions to the immediate forefront. In religious sociology, Millenials and Gen Z’s have already been marked as “nones and dones”, meaning they are no longer religious or never practiced religion because they did not find anything in the institutional church worth committing to. But that does not mean they aren’t spiritual. In this time of physical distancing, we long for something greater to meet the fragility of our humanity. What needs to be put to death in the Church and what is our opportunity for rebirth or resurrection? Indeed we are in an apocalyptic moment.

Millennials and even more so Gen Z care about what we do on a social justice level. How are we as the church addressing the needs of our vulnerable neighbors who do not have masks, or have to work exposed to the virus, or are incarcerated in close proximity or do not have homes to shelter-in-place? Kaiser Health News just reported the exacerbated crisis that many Black and Brown neighborhoods face as the economic and racial disparities impact their exposure and the disproportionately high death rates. We the church have always been called to serve the poor, the oppressed, and the vulnerable, but today this crisis calls for even greater effort on our part and maybe even at our own cost. What is being revealed at this moment?

This leads me to the theological concerns of what it means to be the church in this time in history. The irony of physically distancing to save lives is that now more than ever people are need of physical presence. I have never savored the idea of a hug so much as I have at this point in time. But theologically, physicality is the very nature of the incarnation. Who is Jesus when not incarnational? And who is the church without being that incarnational presence today?

In this time of physical distancing, does our definition of incarnation need to change? Can the incarnation be Zoomed?

There are many other theological questions at this moment, but our need to physically distance is an essential question for a community that has long depended on gathering with one another for identity, purpose, and encouragement.

This leads to the question of what is the prophetic call for the church at this moment? I have struggled to ask my Field Ed students what their vocational call is right now because we truly do not know what the church will look like after this crisis has subsided. In fact, we don’t know what WE will look like after this crisis has subsided. Sheltering-In-Place has forced many of us to face our core beings in such a profound and potentially painful way because many of our coping or covering up devices are no longer available.

I think this is true also for the Church at large. We can no longer hide behind certain things the way we’ve always done them. We are now looking at ourselves and asking, “What is essential”. This question strips away any pretense, any superfluous action, any empty gesture or thinly worn theology. The essentialized church is one that can speak to the present and imagine the future. What do we need to jettison out of budgets in order to meet the needs of people who long for belonging and dignity?

My gut instinct is that the prophetic church today will look a lot like our ethnically dominant churches. These are churches that understand resilience. These are churches with grit. Ethnically dominant churches have had to survive as individuals and as a community at large. They understand how to appropriate resources wisely, how to make a lot with very little, how to survive a crisis, and most importantly, how to depend on one another as if lives depended on it…because they do.

May we as a church learn from this moment in time and live into a prophetic rebirth that will withstand many more times like these to come.

Lastly, to look back to the early church, the Greek word we use to mean the Church is Ekklesia. It was an assembly gathering of people. Our New Testament Professor Dr. Sharon Jacobs informed me that in Greco-Roman times Ekklesia was tied to citizenship. But when they used it to mean church, the meaning extended to women and slaves, people not counted in full citizenship. The imagination of what it meant to gather was expanded beyond the social construct to include more people and extend inclusion to people in the margins.

In our apocalyptic moment for the church, in the middle of Holy Week, in the remembrance of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and in the urgent and imminent questions of who we are as a Church at this moment in history will need to have that same kind of Ekklesia imagination. We cannot be bound by the constructs of our circumstances. We must allow ourselves to let go of what we once knew, grieve those losses, and breathe in the hope and imagination of rebirth for new days to come.